Most people, myself included, know Dorothea Lange as the person responsible for ‘Migrant Mother’, a timeless photograph embedded in American culture. This retrospective exhibition is a chance to witness Lange’s work beyond this iconic image, and to truly appreciate the influence of documentary photography.

Each of the eleven galleries pays homage to a unique project, ranging from the devastating impact of ‘The Great Depression’, to the aftermath of Pearl Harbour in ‘Japanese American Internment’, to America’s transition from poverty to prosperity in ‘The New California’. There is even a gallery dedicated to Lange’s time in Ireland, the only overseas work exhibited.

Whilst the exhibition begins tentative, demonstrating Lange’s portraits of the prosperous individuals in San Francisco during the 1920s, it rapidly comes crashing down. Much like the events of the time, her work goes from feeling fairly light-hearted and non-impactful to driven and courageous.

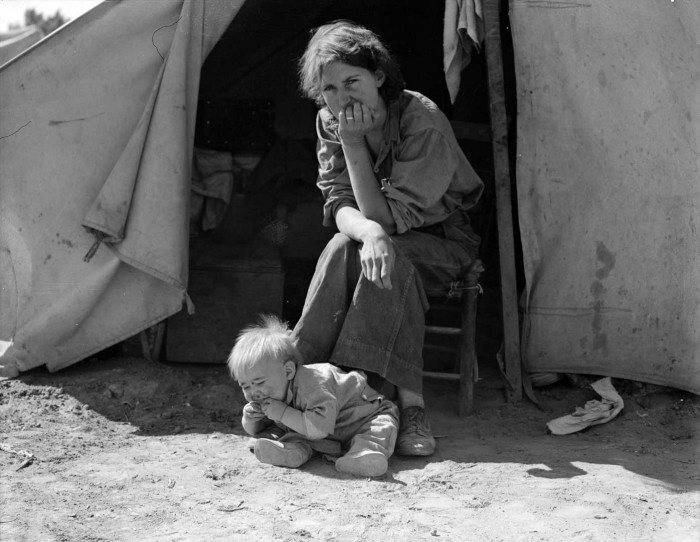

As a result of the Wall Street Crash of 1929 and the severe drought during the 1930s, many Americans had to migrate from what are known as the dust-bowl states (Colorado, Kansas, Texas, Oklahoma, etc.) to more profitable states looking for work. By using the camera as a political tool, Lange aimed to bring awareness of the cruel living conditions of these migrants. Her photos focussed on the context – drought-stricken plains, abandoned farmhouses, desertion – as well as on the individual, highlighting their plight. Whether it be three generations of unemployed men, or a man crippled on the floor in devastation, or a mother trying desperately to stay strong for her children, Lange was determined to humanize migrants and their conditions.

Further on in life, Lange used her influence and her talent to shed light on the Japanese American Internment during World War II. As a result of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour, 1941, Japanese Americans in the United States were forced to relocate and were incarcerated in concentration camps.

The following photo is a particular favourite of mine. As is very characteristic of Lange’s work, it highlights not only loss and injustice, but also a burning sense of pride which clings to much of her work. The people in her photos have endured the circumstances thrown their way.

Offering a more personal perspective, the exhibition has a screening room which focussed on what Dorothea Lange was like as a person. What became clear in this short depiction of her later years was that the photographer had a keen interest in people as well as the ordinary, and she was gripped by the need to communicate what she witnessed to others. There are hints of this attentiveness to the ordinary in her photos. For example, her tendency to focus on particular features, such as a person’s hands. It offers a unique vantage point which enriches her work.

As demonstrated in ‘Dorothea Lange: Politics of Seeing’, Lange pioneered the use of documentary photography. Using her photos as a catalyst for change, she offered a spotlight for those who were suffering, for those who had been wronged, and for those who had been neglected by society for all the wrong reasons. This exhibition has emphasized the power which photos can have, and gives meaning to the phrase ‘a picture is worth a thousand words’.

In the words of Dorothea Lange herself, “the camera is an instrument that teaches people how to see without a camera”. So get yourself to the Barbican and let yourself be taught.

- https://visualhunt.com/f2/photo/3551599565/8738e2da4e/

- https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2018/jun/17/dorothea-lange-politics-of-seeing-barbican-review#img-1

- https://www.loc.gov/resource/fsa.8b31764/

- https://visualhunt.com/f2/photo/5190348074/ff92564589/

- http://encyclopedia.densho.org/sources/en-denshopd-i151-00043-1/

- https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2011/02/jake-jones_-hands-gunlock-utah-1953.jpg